Our contemporary digital existence is so saturated with images—all those TikTok stars and YouTube instructional videos and iOS family photo collections—that it is difficult to recall that for many years the Internet (and the Web) looked like it was going to be all about the resurgence of text. For most of the post-WWII era, the increasingly influential medium of television had suggested that we were headed towards a society dominated by images, not words. But when computers—and particularly network-connected computers—first became part of mainstream culture, they were largely text-based machines. The original architecture of the World Wide Web, conceived by Tim Berners-Lee in the 1980s, couldn’t display still images at all; the idea of watching a video over the Internet would have seemed preposterous back then.

All that eventually changed, of course. For better and for worse, the “image society” has returned with a vengeance over the past decade or two. We don’t think twice about taking a photo of our sandwich and uploading it to the Web; we watch, as a species, roughly five billion YouTube videos every single day. That momentous change was the result of countless innovations in both software and hardware: new standards that allowed us to share photos and videos over the open Web; new high-bandwidth infrastructure; and startups like YouTube and Instagram that popularized sharing images. But one of the most important contributors to the image counter-revolution was an Indian-born computer scientist named Nasir Ahmed, who had an idea back in 1972 that the experts thought was “too simple” to warrant giving him a grant to develop it. Nearly fifty years later, that idea is lurking behind just about every image you see online.

A picture worth a thousand words

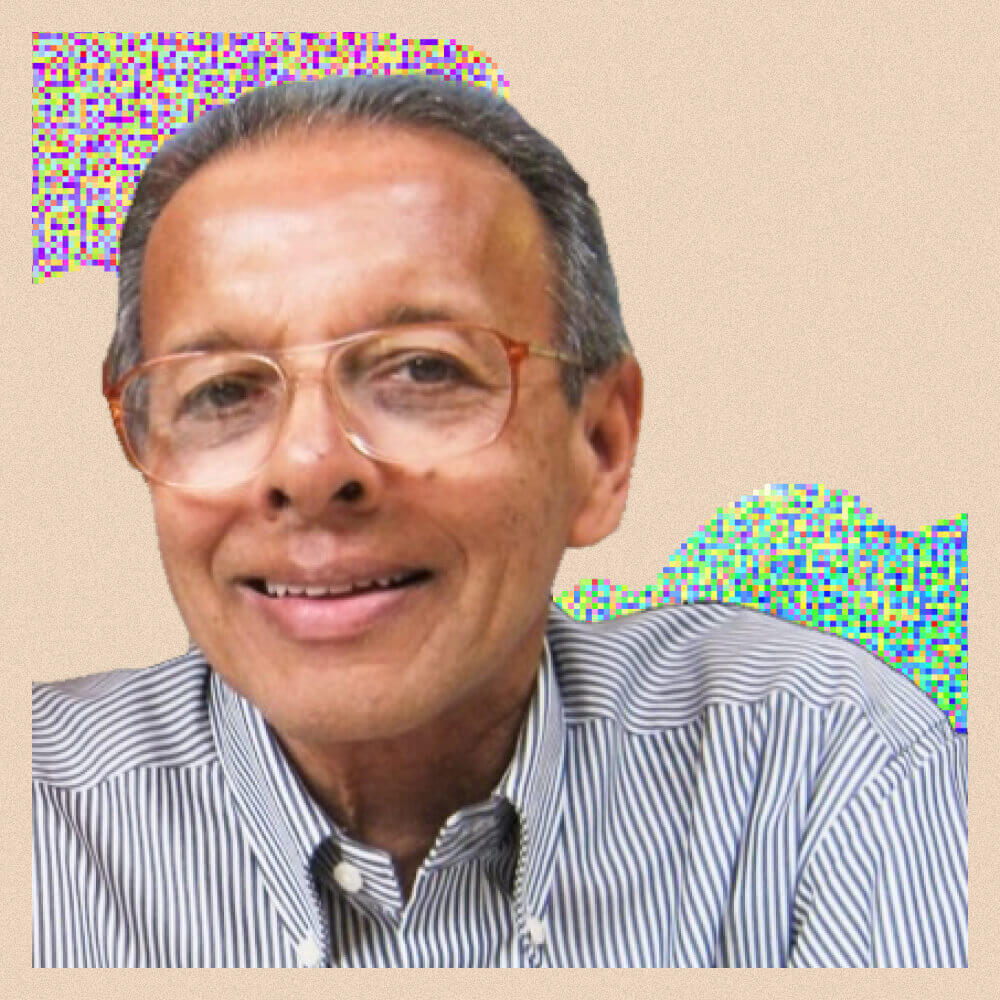

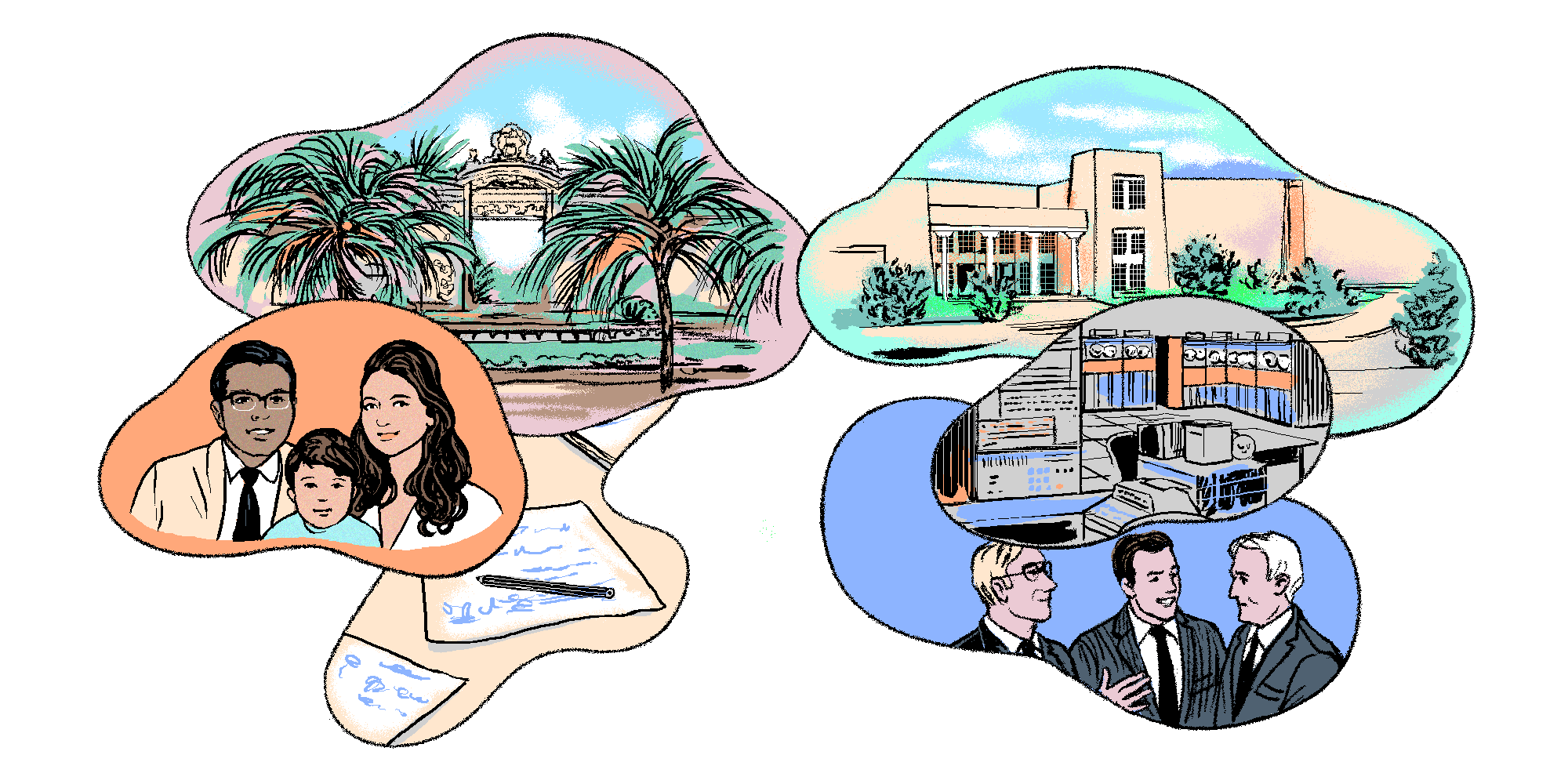

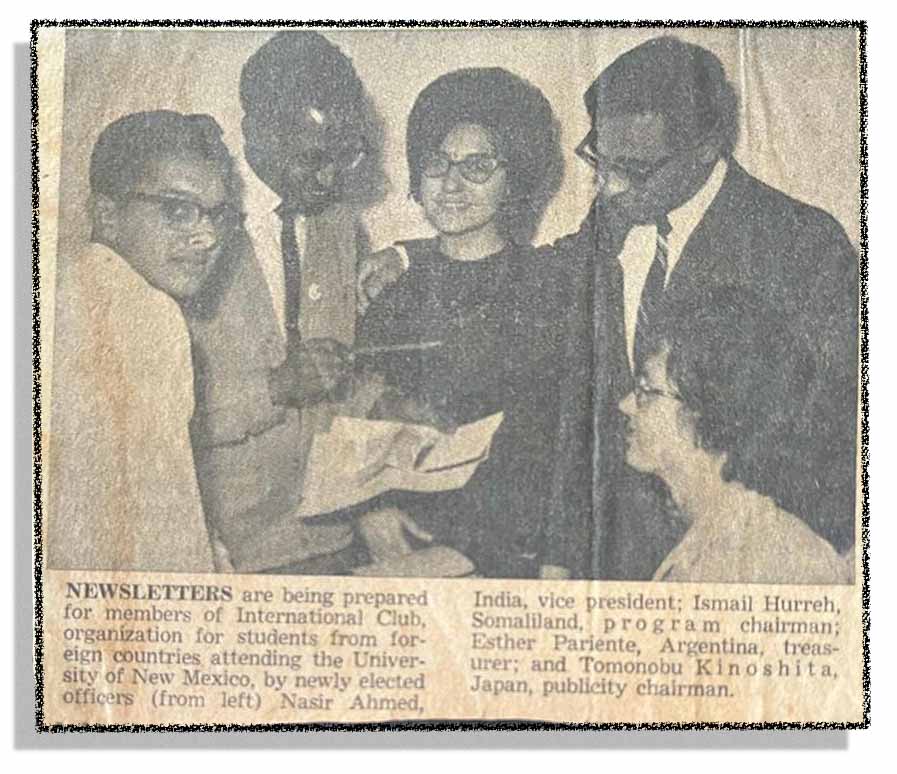

Ahmed was born in 1940 in Bangalore, India, where he was raised by his maternal grandparents. “My grandfather had a tremendous impact on my life,” Ahmed recalls. “He was an electrical engineer, and in 1919 he was sent to Schenectady, NY to work for General Electric. He loved the people and the place so much that he always encouraged me to study electrical engineering and pursue my graduate education in the United States.” Inspired by his grandfather’s words, Ahmed moved to the United States in the early 1960s to do graduate work at the University of New Mexico. As a grad student in Albuquerque, he met an Argentinian emigre named Esther Pariente; the two fell in love and remain married today, 57 years later. In 1966, he briefly took a job at the conglomerate Honeywell which had just launched a computer division to compete with the then-dominant IBM. Even at this early stage in his career, Ahmed was a pioneer of sorts. Today we take it for granted that people of South Asian descent play important roles in the digital revolution. Just look at the org charts of Big Tech companies: currently, the CEOs of Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, and Twitter are all Indian Americans. But when Ahmed first began exploring the world of cutting-edge algorithms, most technology firms in the nascent hubs of Boston and the Bay Area were overwhelmingly—if not exclusively—made up of white Americans.

The recent growth of Indian-American immigrants in the US tech sector has been a dramatic demographic transformation, though it is not often remarked upon. All three of the CEOs—Twitter’s Parag Agrawal, Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, and Alphabet’s Sundar Pichai – emigrated to the United States after being born in India. (In addition to those three, Silicon Valley is represented in Congress by a progressive Indian American, Ro Khanna.) The growth in Indian-American tech involvement applies outside the executive suites as well. While Indian-born people make up about 1% of the US population, they make up 6% of the workforce in Silicon Valley.

Esther Pariente (in the middle). Courtesy of Nasir Ahmed

At Honeywell, Ahmed was first exposed to a technique for analyzing digital signals known as Walsh functions. When he returned to academia several years later, first at Kansas State and then back at the University of New Mexico, he retained his fascination with these cutting-edge mathematical techniques. “We worked both late in the night and again early mornings,” his then collaborator Ram Moran Rao recalled. “That is when we developed mutual interests in the Walsh functions, Walsh transform, BIFORE transform, complex Hadamard transform and as well as the generalized discrete transforms, their fast algorithms and basically their applications.” Those exotic algorithms could serve many purposes: today, they are used in diverse fields that range from speech recognition to radio astronomy. But Ahmed was particularly interested in one specific application: using the tools of signal processing and analysis to reduce the file size of an image without sacrificing too much visual fidelity to the original.

The fundamental problem with digital images is that they contain so much more information than text—at least as measured by the elemental digits of binary code. The ideas embedded in language are encoded at an incredibly efficient rate when we turn them into letters and words. Images, on the other hand, require far more data to do their magic. We all know the saying “a picture is worth a thousand words.” A text file that contains a thousand words is about 5K. An uncompressed photo taken with a high-resolution modern camera can be more than 20MB. To give a sense of the magnitude here, if the text file were a five-story building, the image file would be a skyscraper with 20,000 floors, higher than Mount Everest. A picture may or may not be worth a thousand words—but it definitely requires more information to share it.